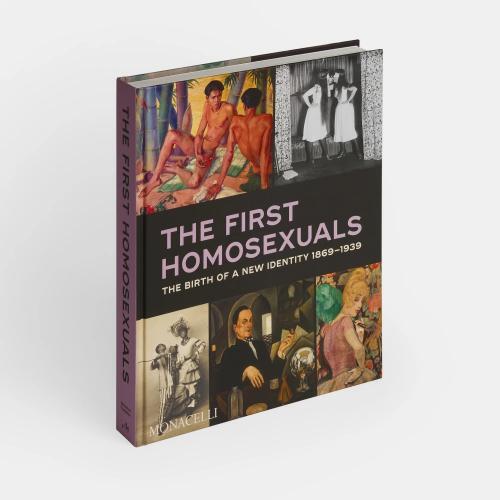

The First Homosexuals

The Birth of New Identities 1869–1939

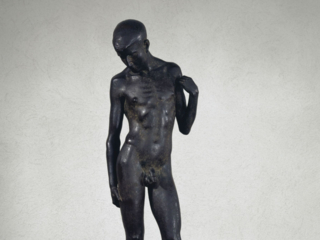

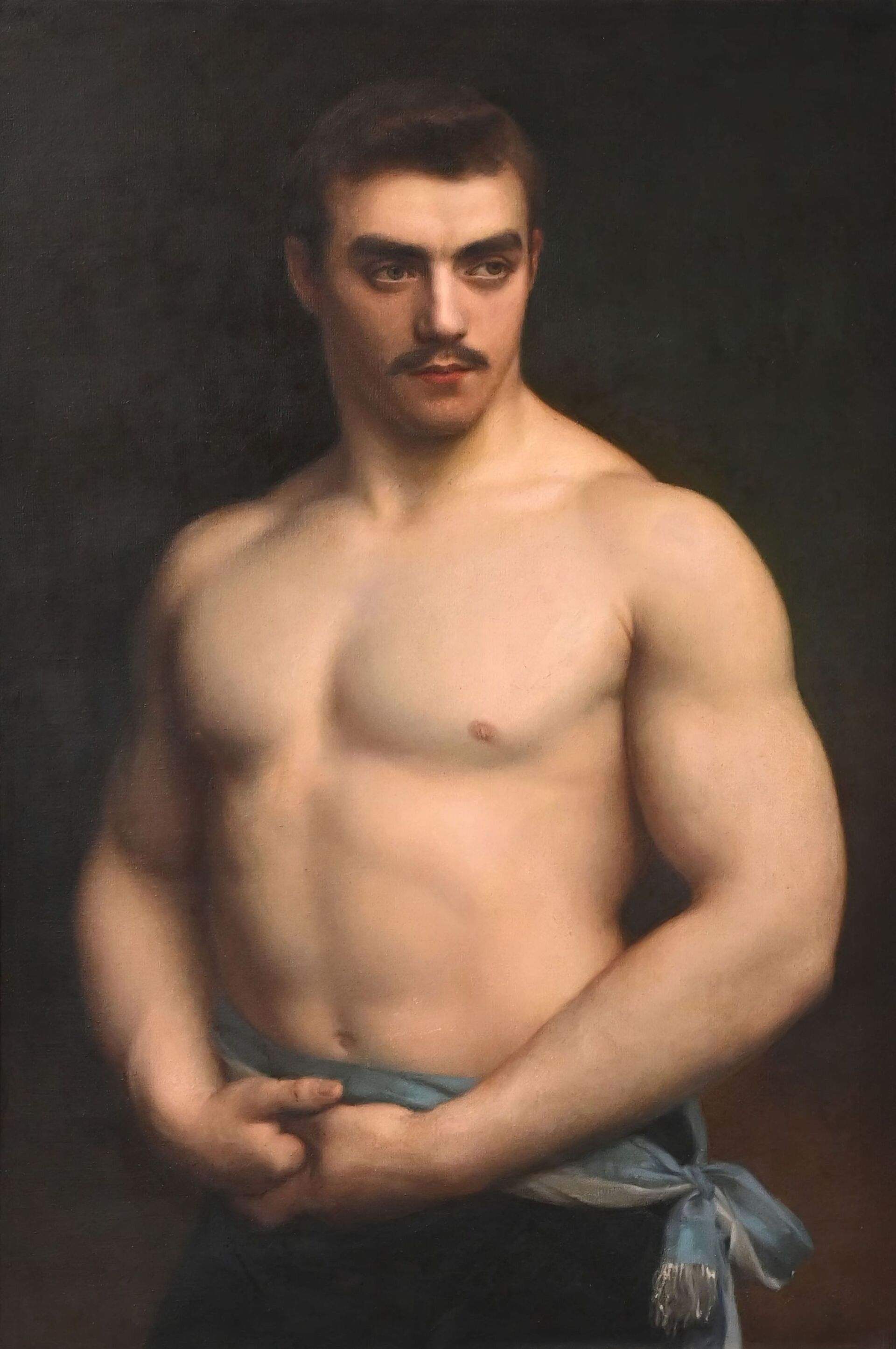

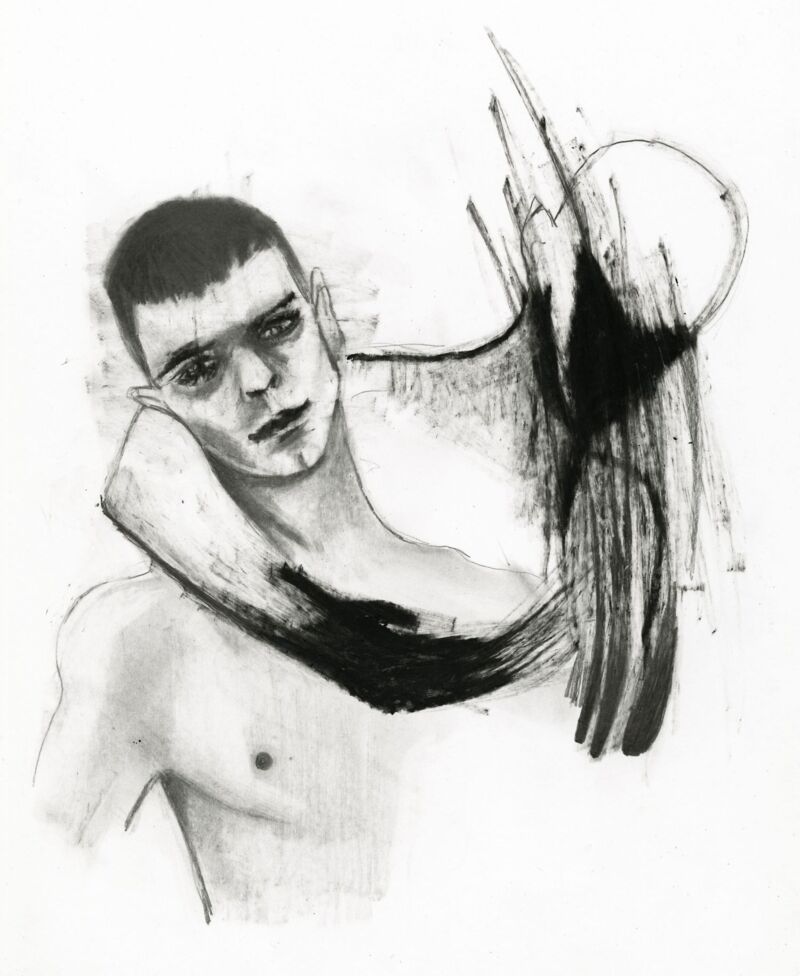

The exhibition The First Homosexuals: The Birth of New Identities 1869–1939 at the Kunstmuseum Basel turns the spotlight on the early visibility of same-sex desire and gender diversity in the arts. Through around eighty paintings, works on paper, sculptures, and photographs, it illuminates how new visions of sexuality, gender, and identity took shape from 1869, the year the word “homosexual” first appeared in print. The multifaceted presentation frames perspectives on queer communities, intimate portraits, bold life choices, coded desires, and colonial entanglements.

The exhibition was first organized by Alphawood Exhibitions at Wrightwood 659, Chicago, where it was researched and curated by Jonathan D. Katz, curator, and Johnny Willis, associate curator. It was adapted for the Kunstmuseum Basel in collaboration with the curators Rahel Müller and Len Schaller.

The term “homosexual” first came into use in the German-speaking world in 1869 and underwent a substantial shift over the following decades. The debate over what the word designated ranged from a universal capacity for same-sex desire to the conception of a “third sex.” The modern terminology originated in a series of letters exchanged by the East Frisian legal scholar Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825–1895) and the Hungarian writer Karl Maria Kertbeny (1824–1882). As early as the 1860s, Ulrichs described the “Urning,” an individual with an innate same-sex desire, a product of their gender variance as they understood themselves to be a third sex, neither male nor female but both. This biological grounding of sexuality shifted the focus away from particular sexual acts and toward an essentialized difference, similar to how we understand homosexuality today. Kertbeny charted a different course. He rejected the idea of an inborn, biological identity and emphasized instead the primacy of a universal human right to desire. In two anonymous pamphlets he circulated in 1869, he coined the words “homosexual” and “heterosexual.”

Gerda Wegener, Lili med fjerkost, 1920, Private collection, Denmark © 2014 MORTEN PORS FOTOGRAFI. All Rights Reserved

The First Homosexuals explores the nascent creative engagement with these themes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In six sections, it introduces visitors to artists and writers who openly grappled with homosexual and trans identities and in some cases also lived them. The presentation retraces the evolution of the nude in connection with changing ideas about sexuality and shows how friendship and familiar motifs from the history of art served as discreet (and sometimes not so discreet) codes for same-sex desire. The show also looks beyond Europe to explore how some European artists attributed same-sex desire to colonial peoples as an inherent flaw—and how, in response, artists around the world challenged and defied this colonial hegemony.

The First Homosexuals reconstructs both the cultural and creative output and the early history of the LGBTQIA+ community. The exhibition and the accompanying publication illustrate how homosexual and trans identities informed each other and retrace the emergence of a distinctive trans identity as given form by modern artists since the introduction of the term “trans” in 1910.

Sections of the exhibition

Events for this exhibition

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

15:00–16:00

Guided tour of the exhibition «The First Homosexuals»

FULLY BOOKED!

Costs: Admission + CHF 7

CURATOR'S TOUR

NEUBAU

18:30–19:30

Kurator:innenführung in der Ausstellung «The First Homosexuals»

FULLY BOOKED!

In German: Mit Kurator:in Len Schaller. Kosten: Eintritt + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

15:00–16:00

Führung in der Ausstellung «The First Homosexuals»

In German: Kosten: Eintritt + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

12:30–13:00

30 Minuten: Das Selbst im Spiegel

In German: Mit der wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeiterin Anna Dedi. Kosten: Eintritt

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

15:00–16:00

Führung in der Ausstellung «The First Homosexuals»

In German: Kosten: Eintritt + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

15:00–16:00

Guided tour of the exhibition «The First Homosexuals»

Costs: Admission + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

12:30–13:00

30 Minuten: Kunst und Aktivismus

In German: Mit Kurator:in Len Schaller. Kosten: Eintritt

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

15:00–16:00

Führung in der Ausstellung «The First Homosexuals»

In German: Kosten: Eintritt + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

HAUPTBAU

12:30–13:00

30 Minuten: Geliebter Radrennfahrer

In German: Mit der wissenschaftlichen Mitarbeiterin Provenienzforschung Katharina Georgi-Schaub. Kosten: Eintritt