Classical Modernism

Collection presentation

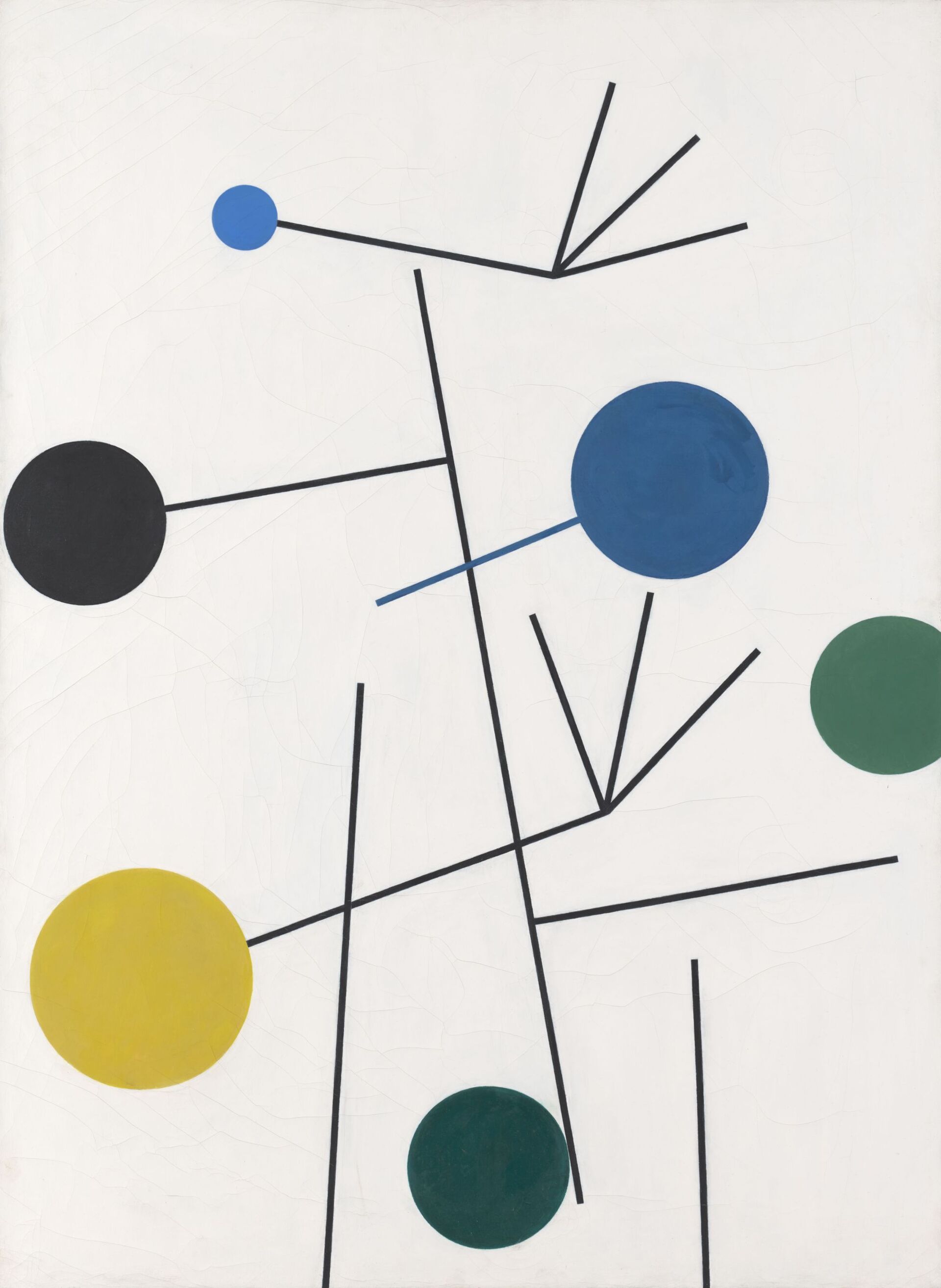

On display in the main building’s second-floor galleries are treasures of classical modernism, including world-famous paintings like Oskar Kokoschka’s Bride of the Wind and Franz Marc’s Animal Destinies. Opening with works by the Fauves and Cubists, the tour continues with galleries dedicated to the art of Expressionism and Surrealism and concludes with the visual language of the Constructivists. The Steinsaal, one of the museum’s finest rooms, invites visitors to immerse themselves in the oeuvre of the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti.

Starting in July 2020, fifteen new works enrich the collection: our presentation of the dazzlingly colorful French art of the early twentieth century is strengthened by outstanding works on permanent loan to the museum, including paintings by André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck. Two galleries devoted to the art of Paul Klee and Pablo Picasso showcase the works from the estate of Frank and Alma Probst-Lauber donated by the Christoph Merian Foundation. Also among the newcomers are not one but two new works by Gabriele Münter: a painting from her early years in Murnau and a reverse glass painting acquired by the Im Obersteg Stiftung. And thanks to another generous donor, a work by Verena Loewensberg now complements the Constructivism gallery at the end of the tour.

Rooms

Works by:

Josef Albers

Hans Arp

Ernst Barlach

Max Beckmann

Max Bill

Georges Braque

Serge Brignoni

Miriam Cahn

Alexander Calder

Marc Chagall

Eduardo Chillida

Giorgio de Chirico

Lovis Corinth

Salvador Dalí

Robert Delaunay

André Derain

Otto Dix

Theo van Doesburg

Jean Dubuffet

Raul Dufy

Helmuth Viking Eggeling

Max Ernst

Lyonel Feininger

Otto Freundlich

Johann Heinrich Füssli

Alberto Giacometti

Fritz Glarner

Julio González

Camille Louis Graeser

Ferdinand Hodler

Alexej von Jawlensky

Wassily Kandinsky

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Paul Klee

Lenz Klotz

Oskar Kokoschka

Maria Lassnig

Henri Laurens

Fernand Léger

Wilhelm Lehmbruck

Jaques Lipchitz

El Lissitzky

Richard Paul Lohse

Verena Löwensberg

Aristide Maillol

Franz Marc

André Masson

Henri Matisse

Joan Miró

Paula Modersohn-Becker

Amedeo Modigliani

László Moholy-Nagy

Louis Moilliet

Piet Mondrian

Kiki Montparnasse (Alice Ernestine Prin)

Edvard Munch

Gabriele Münter

Emil Nolde

Meret Oppenheim

Constant Permeke

Antoine Pevsner

Francis Picabia

Pablo Picasso

Germaine Richier

Jean-Paul Riopelle

Dieter Roth

Henri Rousseau (Le Douanier)

Luigi Russolo

Egon Schiele

Oskar Schlemmer

Georg Scholz

Georg Schrimpf

Kurt Seeligmann

Gustaaf de Smet

Jesús Rafael Soto

Niklaus Stoecklin

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Yves Tanguy

Jean Tinguely

Suzanne Valadon

Kees van Dongen

Georges Vantongerloo

Paule Vézelay

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva

Maurice de Vlaminck

Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart

Fritz Winter

Serge Poliakoff

Adya van Rees