Ghosts

Visualizing the Supernatural

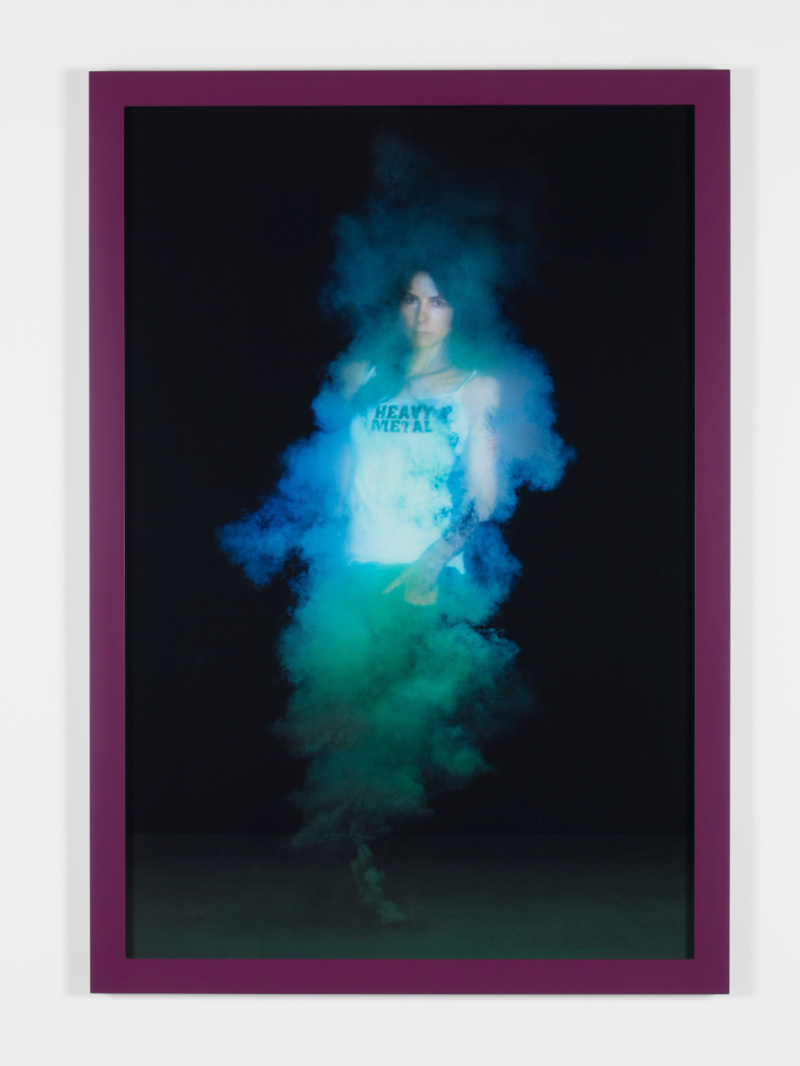

Ghosts seem to be everywhere. Visual culture teems with specters, from Hollywood blockbusters like Ghostbusters (1984) to indie films such as All of Us Strangers (2023). They haunt screens, theater stages, and pages: literature, folklore, and myth are saturated with spirits that refuse to leave us in peace.

They have also always haunted art. As entities of the in-between, ghosts are mediators between worlds, between above and below, life and death, horror and humor, good and evil, visible and invisible. Any attempt to depict, record, or communicate with them thus offers a conceptual challenge and an emotional thrill.

Staveley Bulford, Spirit photograph, 1921, Collection of The College of Psychic Studies, London, Photo: The College of Psychic Studies, London

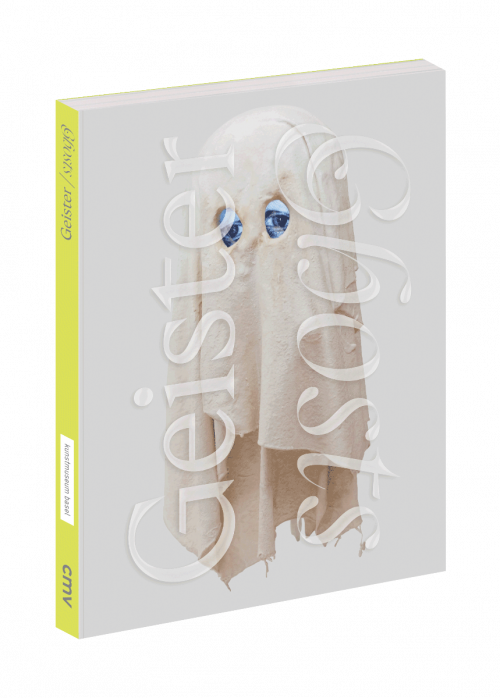

This fall and winter, the Kunstmuseum Basel dedicates an extensive exhibition to these unfathomable entities. With over 160 works and objects created during the past 250 years, Ghosts. Visualizing the Supernatural explores the rich visual culture associated with ghosts that took shape in the Western hemisphere in the nineteenth century—when science, spiritualism, and popular media began to intersect in new ways, inspiring art and artists ever since.

Today, the nineteenth century is mostly regarded as a golden age of rationality, science, and technology but it was also a high season for the belief in ghosts and apparitions. In the second half of the century, ghosts became a tool for probing the emerging contours of the psyche and helped open new paths into people’s inner lives. The Romantic era produced an appetite for spectacles and marvels, and a belief in spirits was flanked by innovations in technology, including in the technologies of illusion (such as the theatrical technique, Pepper’s Ghost).

Benjamin West, Saul and the Witch of Endor, 1777, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. Bequest of Clara Hinton Gould

Hundreds of millions of people all over the world believe in ghosts. Their collective belief has deep historical roots. Although the enormous progress of science and technology would seem to leave no room for ghosts, most people even today retain an attitude of skeptical credence in the supernatural.

The fact that such manifestations interact continually with our collective imagination—our cultural unconscious, even—is what makes the ghost such a powerful and enduring figure and the exhibition a surprising, fun, and thought-provoking journey.

Rooms

Events for this exhibition

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

14:00–15:00

Führung in der Ausstellung «Geister. Dem Übernatürlichen auf der Spur»

In German: Kosten: Eintritt + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

14:00–15:00

Guided tour of the exhibition "Ghosts. Visualizing the supernatural"

Costs: Admission + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

18:30–19:30

Guided curator's tour of the exhibition "Ghosts. Visualizing the supernatural"

With the curator Eva Reifert. Costs: Admission + CHF 7

GUIDED TOUR

NEUBAU

14:00–15:00

Führung in der Ausstellung «Geister. Dem Übernatürlichen auf der Spur»

In German: Kosten: Eintritt + CHF 7