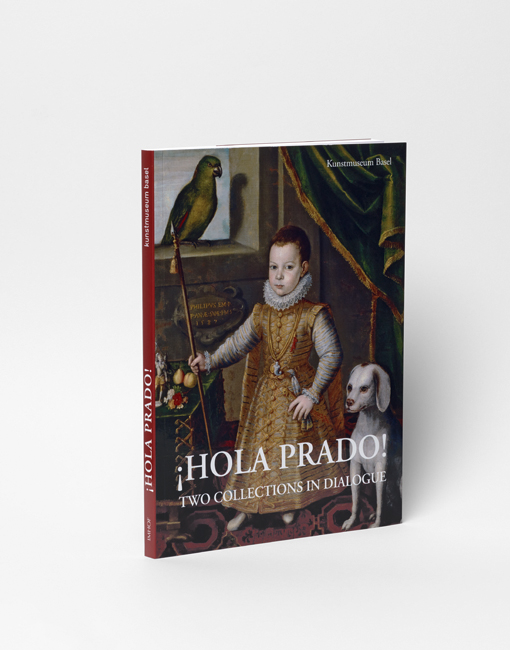

¡Hola Prado!

Two Collections in Dialogue

A return visit between friends and a generous gesture by one of the world’s most significant art collections: In the summer of 2015 the Kunstmuseum Basel lent ten paintings by Pablo Picasso to the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, where they were seen by around 1.4 million visitors. This year, the Prado is repaying the favour by sending twenty-six master works dating from between the late fifteenth century and the close of the eighteenth century on a journey to Basel.

Even such a generous return loan cannot hope to reflect the full richness of the Madrid collection. Therefore, the selection agreed by the Kunstmuseum and the Prado deliberately eschews the attempt to show a cross-section of our respective holdings. Instead, the handpicked guests from the Prado are shown in a sequence of twenty-four focused encounters with a corresponding selection of works from the Kunstmuseum: Titian, Zurbarán, Velázquez, Murillo and Goya appear in dialogue with Memling, Baldung, Holbein the Younger, Goltzius and Rembrandt. Prints by Goya and Holbein the Younger, from the holdings of the Department of Prints and Drawings in Basel, conclude the summit meeting between the two museums. The aim of the exhibition is to identify and make visible the points of connection, bridging artistic, geographical and historical divides, between pictures and collections. A journey of discovery, replete with artistic pleasures, awaits the visitor.

For example: shortly before the Reformation, Hans Holbein the Younger revolutionised sacred art with his depiction of the dead Christ in the tomb, condensing the Biblical narrative into a single still-life image that shifted the categories and boundaries of religious painting. Just over a century later, Francisco de Zurbarán, under the influence of the Counter-Reformation, created a yet more radical picture in the tradition of the bodegones – the Spanish still life paintings with sparse displays of kitchen items in close-up view – showing a lamb with bound feet: the Agnus Dei from the gospel of John, one of the oldest symbols of Christ. Both works implicitly pose the question of how the son of God can be represented in visual terms. In a further picture by Zurbarán, the question becomes a theme in its own right: the painter shows himself in the role of St Luke, addressing the crucified Christ.

The exhibition also presents a secular bodegón from Madrid, which invites comparisons with the sumptuous display of victuals on the table of Georg Flegel from Basel. And Holbein has an opportunity to match himself as a history painter and portraitist with Italian artists such as Titian, whose Ecce Homo confronts Holbein's Flagellation, and Giovanni Battista Moroni, whose Portrait of a Soldier plays the foil to Holbein’s depiction of Bonifacius Amerbach. Further genres are represented by history paintings with religious and mythological subjects, and by allegories and landscapes. The fifty-four works on display are mutually illuminating: by investigating the similarities and differences between them, the exhibition provides a basis for further reflection. In a comparative perspective, it draws attention to correspondences that sometimes become visible at first glance but in other cases emerge only on closer inspection. This is how the history of art is written – or in our view should be written.

The exhibition is supported by:

- Peter und Simone Forcart-Staehelin

- Stiftung für das Kunstmuseum Basel