Inspired by her – Selma Weber

20 Apr 2020

The series of guided tours "Inspired by her" on current female positions at the Kunstmuseum Basel enjoys great popularity. Instead of on site in the house, Iris Kretzschmar now presents the artworks here as text, for example "Bello" by Selma Weber.

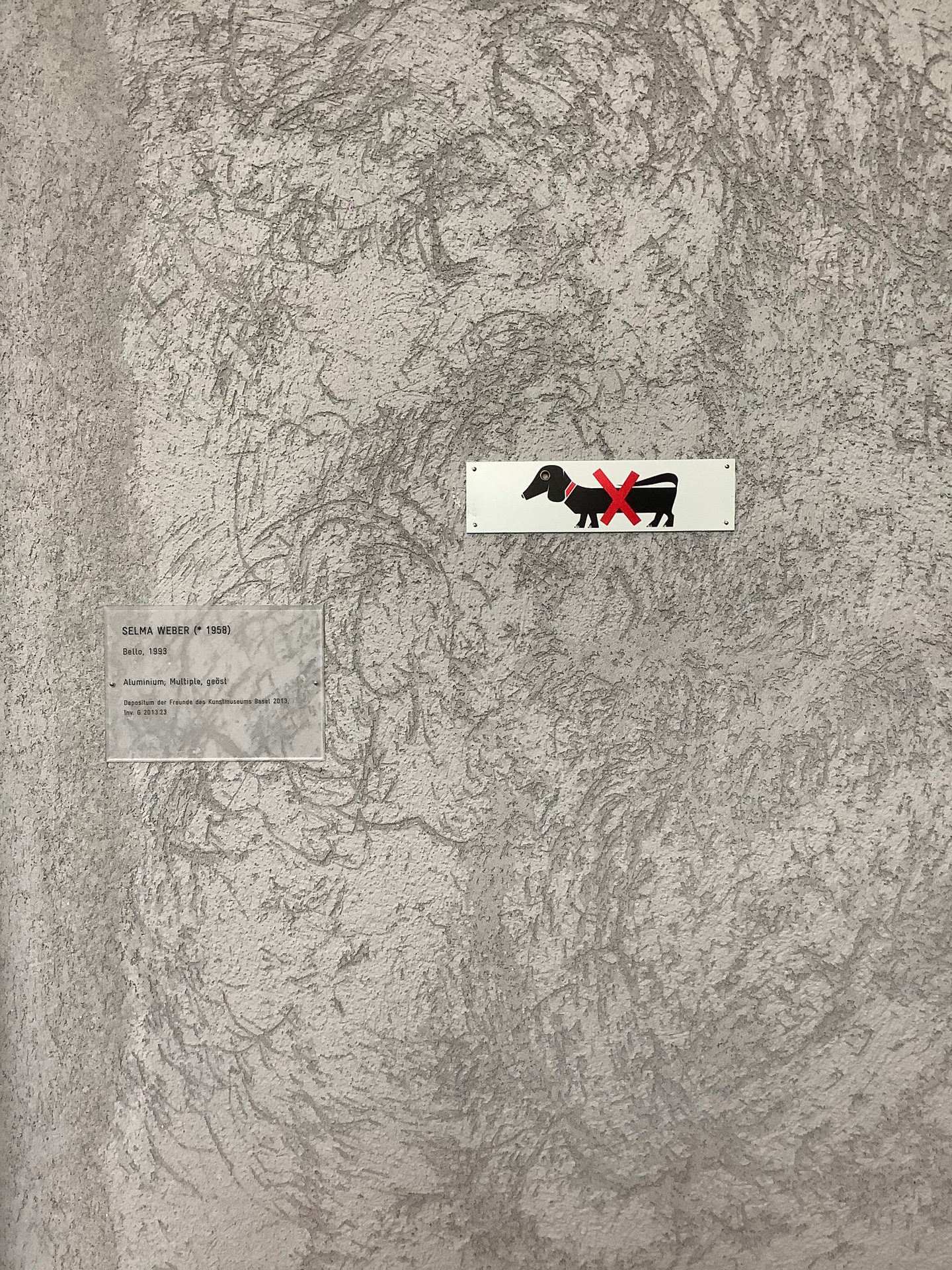

Most people walk past it carelessly – undeservedly. We are talking about a 4.5 x 17 cm small aluminium plate on the wall. It is a multiple by Basel artist Selma Weber (1958) with the title Bello* from 1993. The landscape-formatted plate shows a small black dachshund, with a red collar and a rod placed in front, crossed out by a mighty red cross. Similar signs can be found in many places in the city. Mostly they are pictograms in a reduced visual language, which draw attention to what is not to be done here. How does such a "no dog allowed" sign get into the "holy halls of art", and what is this here?

Bello found his venerable place through the donation of Theresa and Jakob Tschopp-Janssen's collection to the Friends of the Kunstmuseum Basel. Placed with a wink by the director of the institution himself, the sign now inconspicuously adorns a cornerstone between the Hauptbau and the staircase leading to the underpass of the Neubau. What an excellent place, as if made for such an enigmatic hint.

Two heavyweights of art history steal Bello's show on site – the bronze Ptolémée III (1961) by Hans Arp and two monumental, gestural paintings by Georg Baselitz, The Night (1984-1985) and The Lovers (1984). No chance for Bello? Yet it is precisely the discreet hanging in the context of the art heroes that reinforces Bello's subversive effect. If one becomes aware of the little dachshund in spite of the art celebrities, one is first of all surprised, then soon enough one starts to smile. Sure, the dog stays outside, the art is inside? Here you find both. It is a small, targeted and all the more effective trick that allows Bello to assert his presence on the spot. As soon as you take a closer look you will discover the special feature. The eye of the dog has been replaced by a golden glittering eyelet, thus revealing the view of the wall behind it. With this minimal intervention not only the animal and plate are alienated, the object also becomes a refined relief. An exaggeration of the trivial takes place, inviting us to think further.

A look back: in the 90s Selma Weber helped the eyelet, originally a material unrelated to art, to a new aesthetic appeal. Along with Bostitch clips and colorful pins, the use of these small metal rings in pictures and objects even became a trademark of her art for a while. Especially postcards with banal and popular motifs were not safe from her. With devotion she worked the pictures with eyelets, "maltreated" lovely flower greetings with a thoroughly ironic twist.

In 1991, for example, a whole screen of floral eyelet motifs was created. For the installation Adacta (1995) for the Waaghof prison in Basel, the artist, in collaboration with friends, provided 480 briefcases with 312,480 metal eyelets, which were then closed by disabled people. The result was a glittering, movable fan on the wall almost 8 metres long, which is not only visually striking but also questions the system of the prison system with its laborious work.

The origin of Bello also falls into this time. The artist – who herself grew up with two headstrong dachshunds, whose mention still makes her eyes shine today – bought some prohibition signs in the shop to prepare a small edition of the multiple for the annual exhibition at the Ausstellungsraum Klingental in 1993. The idea was captivating, but the effort involved was not too great: according to the artist, four holes were drilled, a large one for the animal's eye and four smaller ones for the attachment. The eye is pushed through the predrilled hole and fastened with a screw press: Bello was born.

Written by: Iris Kretzschmar, art historian, art mediator and freelance author